By Patrick McAndrews

In October 2016, I found myself wandering throughout Joshua Tree, California. I heard about Noah Purifoy’s Outdoor Art Museum and was quickly intrigued. It turns out that Purifoy was a black Alabama-born artist and social worker who was heavily influenced by the Watts Riots of August 1965. His work was largely built from salvaged materials including from the aftermath of those Los Angeles riots. The Outdoor Art Museum in Joshua Tree is where Purifoy spent the last decade and half of his life, creating a massive collection of assemblage art on a 10 acre property in the high desert of California. The property became a museum and continues to exhibit his later works built before his death in 2004.

Since much of his work is large-scale, they are quite prominent in the desert landscape, approaching the property is akin to approaching a small village with a grouping of small homes and shelters. From his Ode to Frank Gehry (2000), to Gallows (2003) and Shelter (1992-1993), Purifoy often uses architectural processes to produce his work. The larger works including Shelter envelope viewers in an immersive experience shrouded in joy, fear, laughter, and despair.

Ode to Frank Gehry lands upon the sand of the high desert as a white alien object. Its textures are an architectural homage to Gehry. Its form almost floats above the ground, seeming to have just touched down like a NASA lunar lander. The white boxy assemblage recalls the Architekton series of sculptures of Russian suprematism artist, Kazimir Malevich. Purifoy, like Malevich, clearly exhibits architectural tendencies, even admitting himself to be an aggrieved architect of sorts.

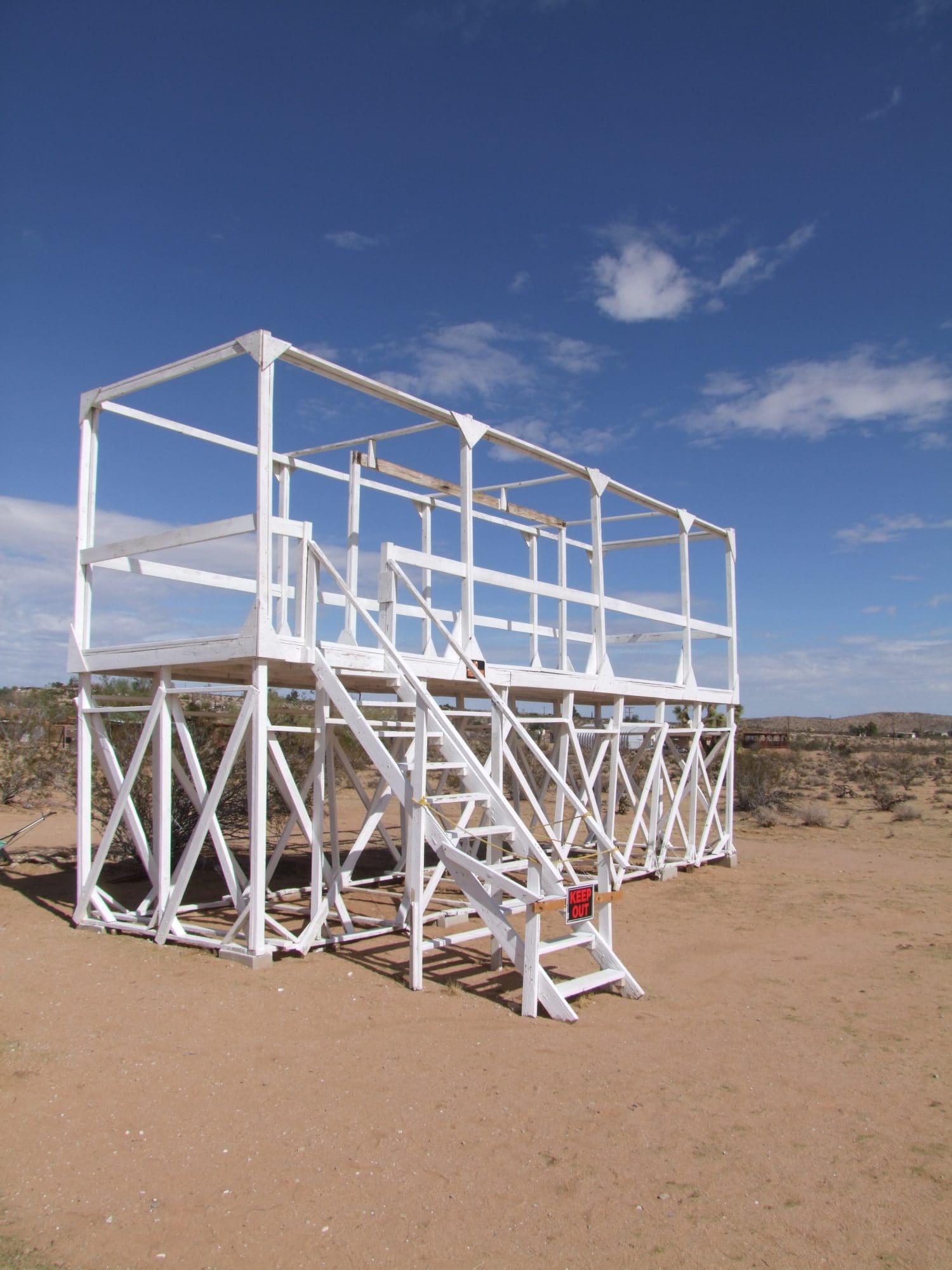

Gallows is a somber and painstakingly vivid reconstruction of a massive gallows scaffold and podium. Although this work has been painted white like Ode to Frank Gehry, it seems to replace authorship and artistry with meticulous and measured authoritarianism. Unlike much of the other work at the museum, there is no mistaking the intensity and intentionality behind its materiality, its design, and its construction. Noah Purifoy’s origins as an African American in the deeply racist culture of the Jim Crow south injects tones of government sanctioned hate crimes onto this white-washed structure.

The Shelter work is one of the many structures intended to be fully immersive. It is an exceptional example of the assemblage construction that Purifoy is known for. Built from the burnt remains of a neighbor’s home, this construction thrusts a perspective of destitute poverty and loss upon those walking through. The walk-through passes meticulously made beds with threadbare quilts, lines of rag-like clothing seemingly hung out to dry, and concluding in a porch-like area with seats and a bookshelf named The Library of Congress. From these charred bits of existential detritus, Purifoy constructs a shelter from tragedy. It is a reminder that while we are an assemblage of our own past experiences, circumstance does not wholly define us. Like Purifoy’s assemblage artworks that re-contextualize human debris, we can choose to compose our human experiences into productive and meaningful narratives to move forward with.

My experience at Noah Purifoy’s Outdoor Art Museum defies summary conclusion, although what I learned of his life and work has stayed with me. I think Purifoy’s art is an outstanding vector for empathy. With pertinent allusions to racism and bigotry, it continues to carry social and political relevance into 2017 and nudges us to take more critical perspectives of our society’s history and future. The sheer volume and variety of work exhibited at the Outdoor Art Museum allow Purifoy’s art to resonate with everyone who wishes to experience and digest even a small portion of this great menagerie in the sand.

What will you see in Noah Purifoy’s work?